In the complex world of humanitarian aid, this collaborative article, drawn from a pivotal session at the Humanitarian Networks and Partnerships Weeks (HNPW) 2025, dives deep into the challenging question: 'How Much Participation Is Enough?'

Authored by insights from the Community Engagement Forum (CEF) and featuring perspectives from the panelists Giovanna Federici (NRC), Jean Marie Ishimwe (R-SEAT), and Yakzan Shishakly (Maram Foundation/CEF Advisory Board), and further enriched by insights from the Forum's Advisory Board members who served between November 2024 and April 2025, including Tom Badham-Thornhill, Nameer Al Hadithi, and Fernanda Baumhardt, this piece confronts the ethical dilemmas, practical limitations, and critical need for genuine engagement with displaced communities. Explore the tension between quality and scale, realistic strategies in challenging access contexts, the evolving role of digital tools, and the crucial responsibility of donors in fostering true participation. This piece challenges the sector to move beyond talk and confront what meaningful participation really requires in displacement settings.

Powerful Insights from the Discussion:

- "Meaningful participation is ethical, but it also makes programmes better – communities help fine-tune what is needed, make aid more relevant and appropriate, and avoid wasting resources."

- "This discussion often ignores the political economy of participation: who pays for it, and who profits from it?"

- "Ultimately, meaningful participation requires courage, culture and system change. It should be an ongoing journey rather than a one-time response."

- "When asking for the time and efforts from already vulnerable people, we must make sure their efforts are benefiting them, not us."

The Core Question: How Much Participation Is Enough?

In today's complex humanitarian landscape, meaningful participation is a priority. But it is rarely resourced, rewarded, embedded in system architecture, or practiced in ways that match its ambition. People tend to talk about participation like it is just the right thing to do - but we rarely admit that it is often a form of unpaid work. When we ask communities to give their time, ideas, and input, we need to think about how we value that. It should not just be about taking from them. Yes, participation is ethical, but it also makes programmes better-communities help fine-tune what is needed, make aid more relevant and appropriate, and avoid wasting resources.

How can we (the humanitarian practitioners) hand over decision-making to the displaced communities without putting displaced community members at risk, or adding yet another burden to already struggling community members? What can we do to make sure there is added value for the displaced from participating? How can we ensure that the right people participate - i.e. avoid tokenistic participation - and how do we support them to be able to participate? In short, how do we make sure the participation is meaningful for the displaced communities and not just organisations ticking a box?

This collaborative article reflects on insights from the Community Engagement Forum (CEF)'s recent session "How Much Participation Is Enough?" at the Humanitarian Networks and Partnerships Weeks (HNPW) 2025, and is intended to contribute to sector wide dialogue on realistic, ethical, and impactful participation in displacement settings. The session provided a timely exploration of these questions, focusing on how these questions can be addressed practically when faced with the realities on the ground that provide multiple challenges to meaningful participation.

Meaningful participation is defined here as participation that leads to project changes that align with the stakeholders' inputs. This definition also implies that participation is traceable in decision-making systems. Humanitarians must be able to show not just that participation happened, but how it changed plans, budgets, or timelines.

The session was structured around three real-life scenarios where the viability for meaningful participation was challenged, and what practical options we have when facing common limitations. This collaborative article delves into the conversation between the panellists Giovanna Federici, Global Project Manager for Community Engagement and Accountability (CEA) at the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), Jean Marie Ishimwe, East Africa Regional Lead for Refugees Seeking Equal Access at the Table (R-SEAT) and Yakzan Shishakly, CEO of Maram Foundation for Relief & Development and an Advisory Board Member of the CEF. It highlights key session takeaways and offers insights into the future of meaningful participation in humanitarian work.

Quality vs. Quantity: The Dilemma of Engagement

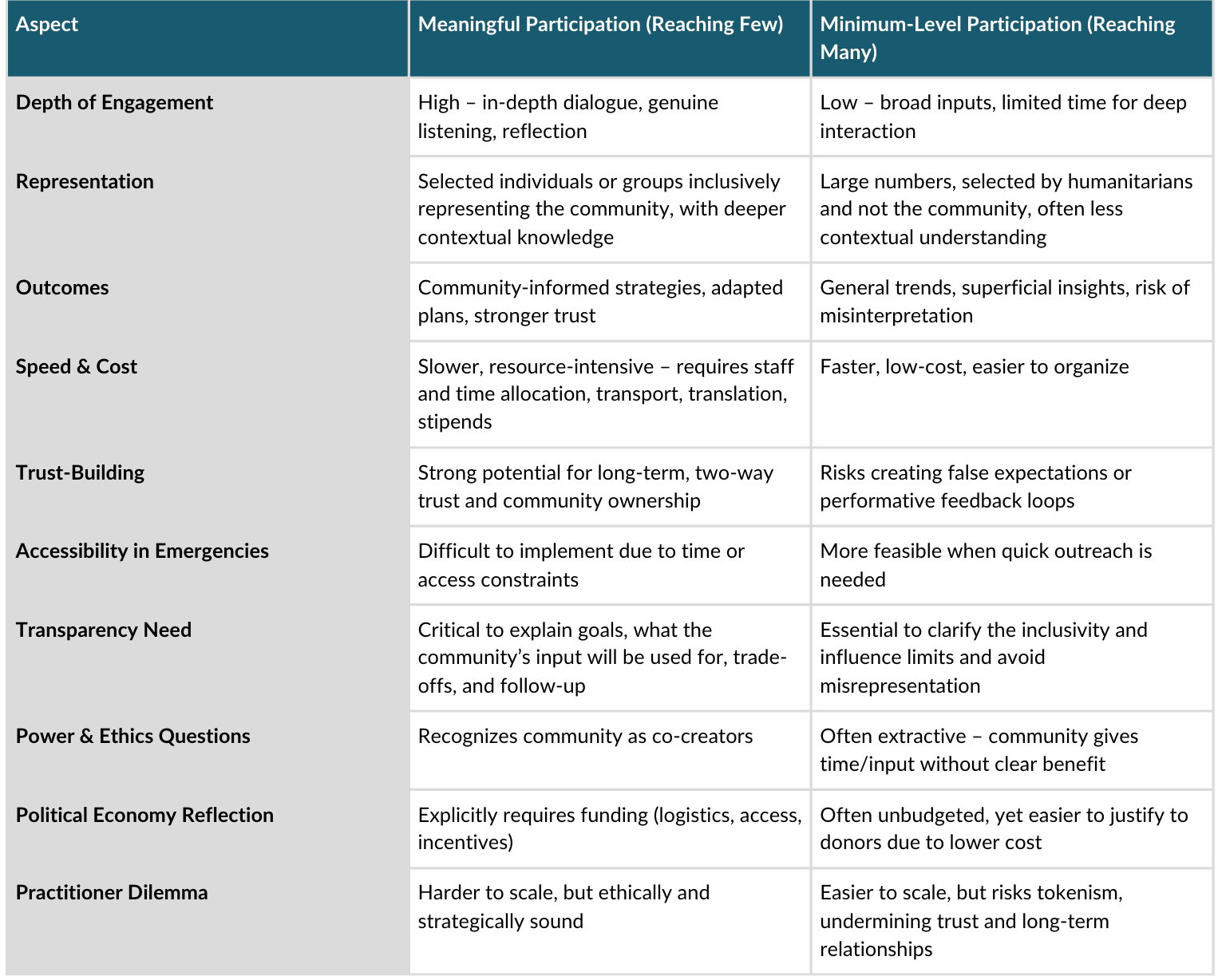

One of the session's central themes was the tension between two approaches to participation:

- Meaningful participation reaching a few: This involves a solid, thorough process with a smaller group of community representatives. This approach allows for in-depth dialogue, genuine understanding, and the formulation of relevant strategies that truly reflect community's needs and solutions.

- Minimum level participation reaching many: In contrast, aiming for lower-level participation may involve engaging with a larger number of people in a more streamlined, less resource-intensive manner. While this approach can cast a wider net, it risks yielding more superficial, agency-controlled insights and provides a false sense of feedback quality and content.

Session participants were divided in their opinions on what would be more impactful. Some said that in situations where meaningful participation is not possible, e.g. due to lack of access to some or all of the displaced community members, or in emergencies, we should aim for lower-level participation activities with accessible community members, as long as we are honest and transparent about our objective and the trade-off between the two. While others questioned who these activities were benefiting, and whether this would work against us as practitioners and undermine our ability to build trust within the community.

This dilemma raised the question "Do we need to go beyond what we see as participation and what that should look like?" Importantly, this discussion often ignores the political economy of participation: who pays for it, and who profits from it? Participation must be budgeted for explicitly, including transportation, translation, digital access, and participant stipends. Without this, meaningful participation remains structurally unfeasible, especially for underfunded local responders.

This discussion often ignores the political economy of participation: who pays for it, and who profits from it?

The panellists emphasised that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Context is key-each humanitarian scenario demands its own approach. Displaced people are not one homogenous group. Different community groups will have different participation priorities. When these do not align with an organisation's technical skills and/or humanitarian principles we need to be transparent and have open dialogues with the people we serve about participation levels, modalities and expectations. This nuanced debate is at the heart of effective humanitarian response and calls for adaptive strategies tailored to specific emergencies.

This also calls for sector-wide operational models that define levels of participation during constraints-e.g. in sudden-onset emergencies, in contested access zones, in displacement camps with fragmented governance. Without such blueprints, staff improvise in ways that reproduce existing exclusions.

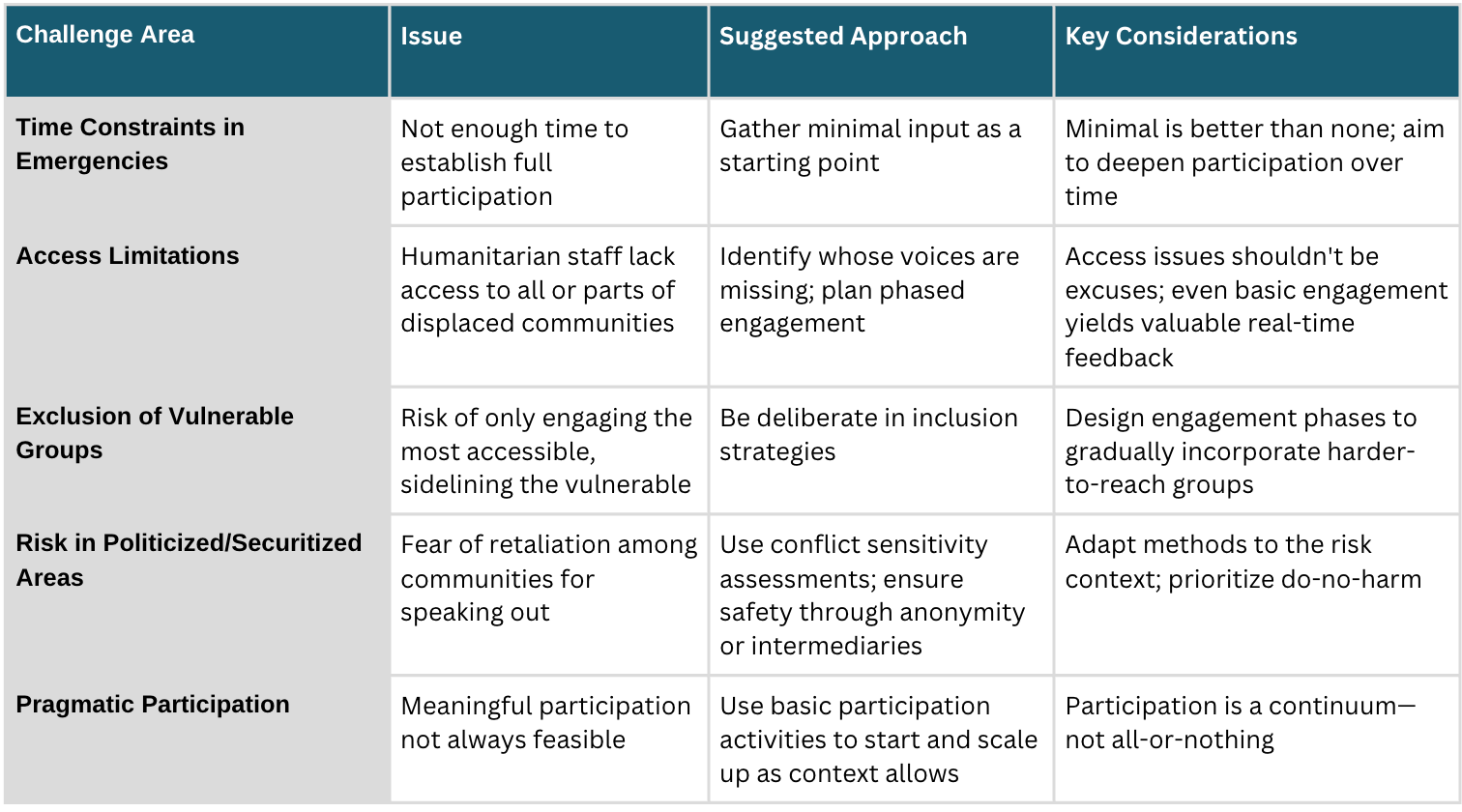

Navigating Challenges: Access, Risk, and Pragmatic Approaches

In emergency situations, time is a critical factor. The discussion highlighted that in crises, there might simply not be enough time to establish a fully participatory process. One suggested solution was that while meaningful participation should always be our aim, gathering even minimal input is far better than no input at all.

Engaging only the most accessible individuals can inadvertently sideline the most vulnerable. Practitioners must be deliberate in identifying whose voices are missing, and plan for phased strategies to include them when conditions allow. In a context where humanitarian staff do not have access to parts of, or all of, the displaced population, meaningful participation may be an unrealistic starting point. Access challenges, however, should never be used as excuses. Even basic participation activities allow responders to gather immediate feedback and adjust strategies in real time, providing a crucial starting point ultimately paving the way for deeper engagement as access improves.

Access challenges, however, should never be used as excuses.

In highly politicised or securitised environments, participation itself can be risky. Community members may fear retaliation for speaking out, especially in conflict zones or under authoritarian rule. Humanitarians must conduct conflict sensitivity and risk assessments for engagement activities-and in some cases, anonymity, indirect representation, or protective intermediaries must be used.

The Promise and Pitfalls of Digital Innovations

Digital tools are reshaping the landscape of humanitarian engagement, and the panellists underscored their potential to overcome traditional barriers. In contexts where conventional consultation methods might be too slow or logistically challenging, digital platforms can complement other modalities by widening access and facilitate more effective communication.

While digital innovations cannot replace in-person engagement, there are several advantages to complementing traditional methods with digital tools:

- Speed and Efficiency: Online platforms can gather feedback quickly, which is essential during emergencies.

- Broader Reach: Digital tools enable organisations to connect with a larger, more diverse audience, even in hard-to-reach areas.

- Enhanced Accessibility: In situations where physical meetings are impractical, digital consultations ensure that community voices continue to be heard.

The panel discussed how digital solutions can be integrated into traditional methods to create a hybrid approach, enhancing both reach and depth. This flexibility is particularly relevant in today's increasingly interconnected world, where technology is central to effective humanitarian response. However, digital engagement cannot be treated as apolitical or universally inclusive. Digital divides persist across gender, geography, disability, and age. Without explicit safeguards, digital tools may replicate systemic exclusions. Platforms must be locally co-designed, privacy-protected, and usable without literacy or connectivity assumptions.

Flexibility and Continuous Dialogue

The complexities of displacement and humanitarian crises mean that no single participatory strategy will work in every situation. Instead, continuous dialogue among stakeholders is essential to refining and adapting approaches as conditions change. The panel stressed that adaptive strategies must be rooted in an open, ongoing conversation between humanitarian actors and affected communities. Mutual trust is a two-way process: not only must community members trust humanitarian agencies, but also humanitarians must trust communities to provide inclusive and representative input and feedback, and act on it. If humanitarian agencies experience access problems in a community, we need to look at why this distrust exists and try to address it in order to facilitate participation.

Community fatigue from extractive consultations is real. People who repeatedly provide input without seeing changes in services, protection, or communication may disengage entirely. Participation must therefore be part of a transparent commitment cycle-communities need to know what was heard, what was done, and what couldn't be done and why. Without this, engagement risks becoming performative.

Donor reporting systems should require feedback loop documentation: what feedback was collected, how it was analysed, what activities were changed, and how these were reported back to affected populations. This moves feedback from symbolic to systemic.

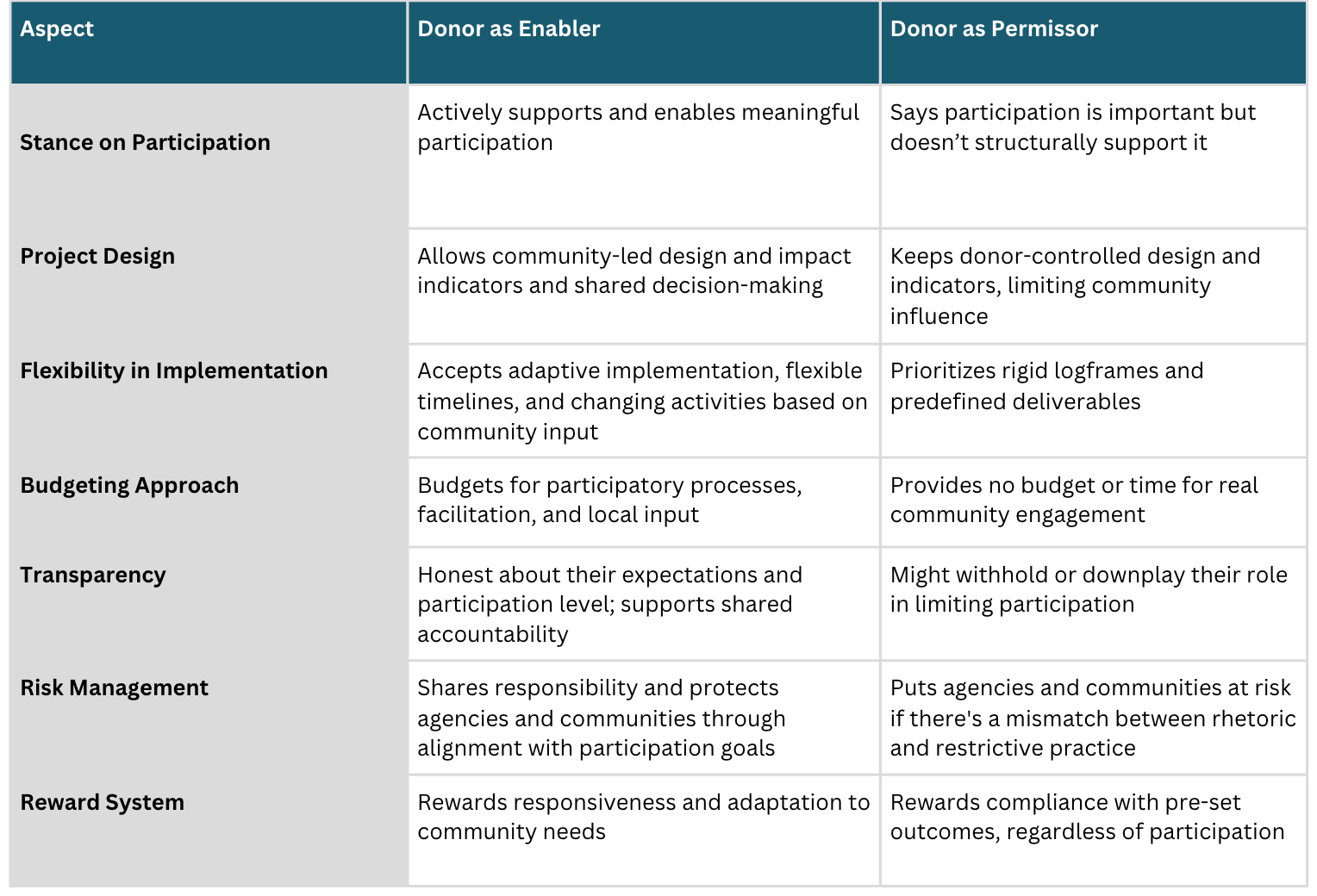

The Critical Role of Donors in Enabling Participation

While many donors aim (and claim) to support and enforce community participation in displacement programmes, if they do not follow through on their stated intentions, they could end up putting the implementing agency and potentially also community members at risk. A donor-controlled project design will never fully allow for meaningful participation of the project participants. Discussion around the donors' role highlighted that if donors will not support project decisions to be based on participatory input, donors and implementing agencies need to be transparent about their limited participation approach and the level of participation they are willing to support. If, however, donors claim to support meaningful participation, they need to also allow for the necessary project flexibility - this includes budgeting for community-led design processes, accepting adaptive implementation, and rewarding responsiveness over rigid logframes.

If participation is a requirement, donors must make it possible, not just permissible.

Conclusion: Participation or Pretence?

This discussion serves as a powerful reminder that participatory decision-making in humanitarian response is both complex and crucial. And that how much is enough has no easy answer. In short, the illusion of participation can eclipse dangerous project limitations and inappropriate activities. It demands time, trust, and flexibility - elements that are often sacrificed to speed, scale, and donor requirements. In situations where meaningful participation is not possible it is better to be open about this and do our best to facilitate participation activities while taking all the steps we can to ultimately hand over decision-making to the displaced population. Emergency situations can be challenging, but recovery and preparedness phases provide us with a chance for community-led planning. During these calmer times, we can focus on building trust, training local facilitators, and creating systems for swift engagement in future crises. Ultimately, meaningful participation requires courage, culture and system change. It should be an ongoing journey rather than a one-time response. Ignoring the dilemmas faced by practitioners is just as harmful to the participation revolution as inaction. We need to continue the open and honest conversation around meaningful participation if we want to achieve this. When asking for the time and efforts from already vulnerable people, we must make sure their efforts are benefiting them, not us.

"Ultimately, meaningful participation requires courage, culture and system change. It should be an ongoing journey rather than a one-time response."

For those who missed the session, the video recording is available here: Full Session Video